Cigarettes - Chemical Furnaces That Make Toxic Smoke

The packages say it all. Smoking cigarettes kills - and it does so in some of the most gruesome and insidious ways imaginable. Your lungs and heart get eroded, the liver clogs up with toxic chemicals and the nervous system loses its efficieny as a degrading cancer slowly colonises your body from one organ to another. Then, suddenly, you're faced with a myriad medical conditions that either take a horrible amount of effort and money to assuage - or simply plague you for the rest of your (probably shortened) life. Not something I would ever recommend doing.

What I would recommend, however, is researching and taking into account how these conditions are brought about in the first place. What exactly is it about lighting cigarettes and inhaling their smoke that causes such severe consequences, even when it does not feel that bad when you try it out (according to some people who smoke/used to smoke who I spoke to)? If you are more knowledgeable about the subject, after all, you can more smartly and informatively advise others to either quit or not begin in the first place. The short idiom 'know your enemy' goes well here. And so this is the topic for today's post; taking an investigative look at the carcinogenic chemistry behind smoking.

Lighting It Up

When you first start burning a cigarette, its design and chemical composition inside can influence the chemicals that start flowing out of it as smoke. To distinguish between different parts of said smoke, we label the amalgamation that flows out of the peripheral end of the rod (where it's lit) as the sidestream smoke and the one that is directly inhaled by the smoker through the back of the rod as the mainstream smoke. It should also be noted that, when we use the term 'smoke', it refers to a chemical mixture of both a gas phase of matter (such as nitrogen gas) and fine liquid particulates that are suspended by the atmosphere around them (such as nicotine molecules). In order to identify the chemical species that make up this mixture, scientists have used micrometer-sized pores on glass fibre filters to separate the gas and particulate phases into impermeable containers, ultimately finding particulates that are usually synthesised from burning coal and fractionating crude oil.

In total, researchers have found over 7,000 compounds from a variety of different chemical classes present in tobacco cigarette smoke, with others claiming that there are still thousands more that are yet to be uncovered. Many of these are not originally present in unburned cigarettes, and only become present once the fuel inside (which is most concentrated in the rod's center) has started to burn and combust - similar to the complex combustion of wood that occurs during wildfires. Nonetheless, the species that have been detected should give an indication of the harm that smoking can bring. Some compounds in cigarette smoke include: cyanide, ammonia, carbon monoxide, arsenic, lead, N-nitrosamines, paraffin waxes and cancerous polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Though these compounds vary in size and effect, all are harmful and potentially lethal when inhaled in high concentrations - such as carbon monoxide, which can bind to blood haemoglobin and lead to a lack of oxygen transport around the body, essentially suffocating body cells.

Studies have shown that the way that a cigarette is puffed and the spread of chemicals along its body can further influence the compositional compound ratios between mainstream and sidestream smoke. For instance, puffing more frequently and more strongly heats up the periphery of the rod to temperatures of up to 900ºC, thereby combusting tobacco at the periphery and mixing it into the mainstream smoke (as the generated smoke flows back into the vacuum inside the cigarette when one inhales, thereby leaving the rod at back). Comparatively, not puffing decreases the cigarette's temperature to about 400ºC, inducing more of the chemicals in the centre of the rod to burn, instead. Since, in this scenario, the smoker is not sucking in the smoke generated by the burning tobacco, it then diffuses through the front of the rod and comes out as sidestream smoke - and it is generally in far greater quantities than the mainstream smoke. Furthermore, the fact that this occurs at a lower temperature than mainstream smoke means that bigger quantites of unstable and/or toxic substances like carbon monoxide can be found in sidestream smoke. In reality, smoking at a particular time causes the worst damage not to the smoker - but to the victims in their vicinity.

Invisible, Scentless And Deadly

To avoid passive smoking, always be wary that most of the gas produced by smoking cigarettes is, in fact, invisble to the naked eye. Much of it also does not carry any smell or any taste, and can very easily be inhaled without you noticing. Either way, since most of the smoke created diffuses away from the cigarette, it is an unfortunate irony that a smoker is normally safer from it than a passerby in front of them would be. There is evidence for this - along with a terrible amount of precedence.

According to the NHS in the UK, people who take in second-hand smoke are more likely to derive the same medical conditions as active smokers, including diseases like heart disease, lung cancer, asthma, and even new allergies. Many breathing problems in children are often the result of passive smoking caused by smoker parents, with pregnant women being particularly vulnerable to it due to it being able to cause defects (and even deaths) in babies. Personally, I would recommend always trying to circumvent smokers when you come across them on the streets, or at least holding your breath for the time that you pass them.

As I have discussed the composition and spread of cigarette smoke, I would now like to give you a few details about how some of the chemicals involved are even toxic in the first place. For example, why can inhaling PAHs increase your risk of cancer so dramatically? And what is tar? Why does it build up in your ventilation system as you smoke? Let's find out.

The Toxicity Of Cigarette Smoke

Some of the chemicals in cigarette smoke that present the highest risk of cancer, according to the CDC, are molecules known as 1,3-butadiene, benzene and benzopyrene. All three of these are able to react with a large number of important biological molecules in our cells - including DNA - and can therefore essential metabolic pathways involving them from taking place. Worse, they can also only change how the pathways occur.

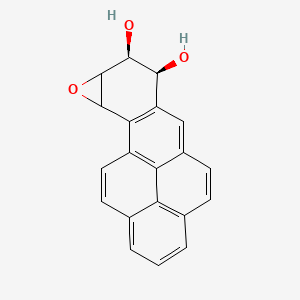

Take benzopyrene. This molecule is a good example of a PAH, and much research has been done in the effects of introducing it to our body. Interestingly, when it enters the bloodstream, benzopyrene does not immediately act as a carcinogen. Instead, it stays docile and relatively unreactive for a bit; when enzymes start working on it, however, the story changes. As benzopyrene flows through the body, it can react to form benzopyrene 7,8-oxide, which might be oxidised by epoxide hydrolase enzymes in the liver into benzopyrene-7,8-dihydrodiol. Normally, epoxide hydrolases work to detoxify harmful chemicals in the blood into safer diol varieties, and such is the case with benzopyrene-7,8-dihydrodiol - but here's the catch. This particular diol is actually a precursor for even more cancerous products and, by some unfortunate coincidence, the liver also contains enzymes referred to as cytochrome P450 enzymes that can metabolise it in exactly this way. Ultimately, this ends up producing the king of all carcinogens - benzopyrene-7,8-diol-9,10-epoxide (BPDE).

BPDE is labelled as a carcinogen because it can not only join and react with DNA to cause mutations - molecules that can do this are generally known as mutagens - but because these mutations specifically affect genes that are involved in cell division and cell death. Such mutations rarely incite cancer, as cells are amazingly well adapted for quality control, repairing and managing their genetic information whenever they encounter a problem with it - or killing themselves if even that doesn't work. If you continue absorbing carcinogens for long periods of time, however, the quality control will eventually skip some minor errors in the process. These accumulate and affect each other nigh-on exponentially, until one day you find that a patch of mutated cells has steadily been growing inside your lungs - and outside them, too, if the situation has worsened too much.

Alas, BPDE is only the start of the list of carcinogens in cigarette smoke. Indeed, over 70 chemicals found in tobacco smoke are classified as such. Furthermore, BPDE, benzene and other large molecules - the particulate phase matter especially - can form what you might know as cigarette tar. Though this is not the same tar that people use to make roads (consuming that, I think, would probably kill you very quickly), it is nonetheless horribly bad for your lungs and trachea and only gets worse when it starts entering the bloodstream. To put this into perspective, there are actually videos online that show the formation of cigarette tar in transparent containers - and it is not pretty! Do watch one if you're curious; it is both frightening and really disgusting.

So, to recap: smoking is awful for you, the people you live with and everybody that you come across outside. I know that nicotine makes smoking addictive and difficult to stop once you've begun, but there are many nicotine alternatives that are there to help - from chewing gum and nasal sprays to sublingual pills. For now, though, take care of yourself!

References

- CDC (2010). How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease: The Biology and Behavioral Basis for Smoking-Attributable Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General. CDC. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53014/

- Rodgman, A. & Perfetti, T. (2013). The Chemical Components of Tobacco and Tobacco Smoke, Second Edition. CRC Press. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/294261056_The_Chemical_Components_of_Tobacco_and_Tobacco_Smoke_Second_Edition

- Apostolou, A. et al (2012). Secondhand Tobacco Smoke: A Source of Lead Exposure in US Children and Adolescents. American Journal of Public Health. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3489360/

- NHS (n.d.). Passive Smoking. NHS. Retrieved from https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/quit-smoking/passive-smoking-protect-your-family-and-friends/

- Rourke, J. L. & Sinal, C. J. (2014). Encyclopedia of Toxicology (Third Edition): Biotransformation/Metabolism. Academic Press. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/benzoapyrene-7-8-dihydrodiol-9-10-oxide